Architect Susanka champions “not so big” approach

McMansions, those suburban Titanics cruising on chemically enhanced lawns from Maine to California, are a durable symbol of American excess. The environmental punditocracy hates them, and as far back as 2005, The New York Times reported that the McMansion era was waning. That turned out to be wishful thinking, but a lot has changed in the ensuing years. More recent studies by the American Institute of Architects and the National Association of Home Builders, reported in the Wall Street Journal, suggest the McMansion backlash is for real this time. To find out why, you can’t do any better than asking Sarah Susanka, author of the book “The Not So Big House” and its sequels. First, though, let’s examine our quarry.

McMansions, those suburban Titanics cruising on chemically enhanced lawns from Maine to California, are a durable symbol of American excess. The environmental punditocracy hates them, and as far back as 2005, The New York Times reported that the McMansion era was waning. That turned out to be wishful thinking, but a lot has changed in the ensuing years. More recent studies by the American Institute of Architects and the National Association of Home Builders, reported in the Wall Street Journal, suggest the McMansion backlash is for real this time. To find out why, you can’t do any better than asking Sarah Susanka, author of the book “The Not So Big House” and its sequels. First, though, let’s examine our quarry.

“McMansion” is often used as an unflattering synonym for any big house. That’s wrong. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a big house. The problem is big and wasteful. A true McMansion is a homily to wasted space. You enter the average McMansion through a foyer that needs only a teller line and an ATM machine to make a smashing bank lobby. The ceilings in every room soar to nosebleed heights. There is a formal dining room to go with the eat-in kitchen and the breakfast nook. Grandma needs a golf cart to make it to lunch from the guest room, which is occupied a total of three weeks per year.

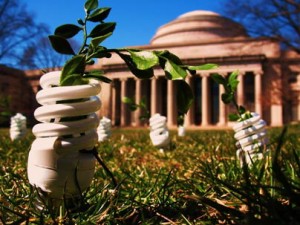

Building this wasted space consumes materials and energy, which is enough of a price tag, but the long-term cost is even worse. McMansions promote energy waste and pollution. They consume electricity and oil to light, heat and cool space the owners can’t actually live in, which is why the McMansion era’s end would be great news for the environment. But how can we be sure it’s really ending? There have been earlier predictions of their demise. What’s to be done with the thousands of McMansions sucking up energy across the country?

Building this wasted space consumes materials and energy, which is enough of a price tag, but the long-term cost is even worse. McMansions promote energy waste and pollution. They consume electricity and oil to light, heat and cool space the owners can’t actually live in, which is why the McMansion era’s end would be great news for the environment. But how can we be sure it’s really ending? There have been earlier predictions of their demise. What’s to be done with the thousands of McMansions sucking up energy across the country?

Susanka, a Minnesota-based architect who has been writing and speaking about the “Not So Big” concept since the 1990s, sees signs that this time, the McMansion is getting a permanent “to go” order.

“I think something pretty dramatic has shifted in how we see things, how we invest money and how we buy,” Susanka said from her architectural firm’s office in Minnesota. “The reason I’m saying that now is because our collective confidence level has been deeply shaken by the economic downturn in a way it hasn’t for a generation. For a long time before the recession, there was a lot of impetus for building McMansions because it was easy to get mortgages for larger homes. Today, all the bankruptcies and foreclosures have made a lot of people stop and think more about how they want to live. Since 1929, we haven’t had something that hit home this hard, making people wish they had more savings and had not overspent to the degree they did. That put their worlds into a new framework.”

That new framework, she says, will encompass a new attitude toward home construction. Rather than reflexively building rooms that get little use, like formal living and dining rooms, Susanka says consumers in the post-recessionary economy are more likely to seek houses designed around the way they live, and not a one-set-of-rooms-fits all floor plan. For a casual family, a formal living room is a waste. The “Not So Big” approach would be to build a slightly larger family room with a small “away” space for privacy. Don’t do formal dinners? Forget the formal dining room. Build a bigger kitchen with a multi-purpose eating area. Have occasional guests? Install a Murphy bed in your home office so it can double as a guest room. And enough with the 22-foot ceilings, unless your pituitary gland has gone haywire. Instead, Susanka says, use varying ceiling heights to define space in a way that makes less square footage seem just as roomy.

“Touches like that help a house feel big but not be so large,” she said. That’s a key point. Susanka and other like-minded architects aren’t trying to shoehorn us into 400-square-foot garden sheds. The homes in her books are spacious, airy, and classy. They’ve taken resources away from wasted space and put it into durable, useful features like built-in bookcases, cabinets and window seats. In other words, more storage in less space.

A shift in attitude toward home design will take care of the future, but what of the existing ranks of McMansions, and ongoing energy drain? Susanka points to another generation of house that could have become white elephants but for economic necessity and American ingenuity.

“Look at the Victorian era, where we had a similar pattern of development. Houses got bigger and bigger because families had servants and it was a more formal era. They needed formal dining rooms and butler’s pantries and parlors. When the era passed, many of those homes were big enough to break up into duplexes and triplexes. That’s entirely possible for McMansions,” she said. “They can be remodeled to make better use of existing space so they don’t consume as much energy. It can be relatively inexpensive to do.”

Giving McMansions a new life as multi-family homes is the best solution for the environment. Knocking them down would be a waste of energy and building material. Turning them into a new era of Victorian multi-family homes will add more affordable housing to the country’s stock, reduce energy consumption, and maybe even put the “Mc” back in front of “Donald’s,” where it belongs.