About eight years ago, one of my best friends scoffed at my newly purchased electric lawnmower and even louder at the reason I bought it. I had decided against a new gas-powered mower because I had read how much junk their two-stroke engines release into the atmosphere. My friend said that my electric lawnmower was no more environmentally friendly than his two-stroke mower because they both burned fuel, just in different places. His lawnmower did it in his own yard, while mine did it at coal-fired power plants here on the New Hampshire Seacoast, the source of my mower’s electricity.

Full disclosure: My buddy is not exactly objective when it comes to green issues. He’s about as environmental as a barrel of dioxin. He sells building materials and one of his favorite jokes is “I love spotted owls. They’re all we ate on the baby seal hunt.” You get the idea. So maybe he was dissing my lawnmower to get even with me for the year I gave his daughter a copy of “The Lorax” for Christmas, but he had a point. It’s a point society has to address as products like plug-in hybrid cars hit the market making claims at green cred. For example, General Motors is staking a lot on its soon-to-be released Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid. If, however, buyers don’t see economic and environmental upside in the Volt and its ilk, these products are going nowhere. It’s a given that plug-in hybrids burn less gasoline than their internal combustion-only cousins, but they don’t necessarily consume less energy.So they can’t be much better for the environment, right?

Full disclosure: My buddy is not exactly objective when it comes to green issues. He’s about as environmental as a barrel of dioxin. He sells building materials and one of his favorite jokes is “I love spotted owls. They’re all we ate on the baby seal hunt.” You get the idea. So maybe he was dissing my lawnmower to get even with me for the year I gave his daughter a copy of “The Lorax” for Christmas, but he had a point. It’s a point society has to address as products like plug-in hybrid cars hit the market making claims at green cred. For example, General Motors is staking a lot on its soon-to-be released Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid. If, however, buyers don’t see economic and environmental upside in the Volt and its ilk, these products are going nowhere. It’s a given that plug-in hybrids burn less gasoline than their internal combustion-only cousins, but they don’t necessarily consume less energy.So they can’t be much better for the environment, right?

There is an answer to that knock against plug-ins, but government has to supply a critical missing piece before the answer stands up to scrutiny. The answer is based on the difference between point and non-point sources of pollutants. Power plants are “point” sources of air pollutants. Cars, lawnmowers etc. are “non-point” sources. It’s a distinction lost on most people, including my owl-munching friend. (I’m pretty sure he was just kidding about the owls, but I couldn’t swear to it.) This distinction gives plug-in hybrids the potential to change our transportation energy consumption habits for the better.

Point-source pollution is easier to manage than non-point source pollution because it’s easier to equip one power plant with effective pollution control technology than to equip 100,000 cars. Today’s emission control technology can remove up to 80 percent of the toxins, greenhouse gases and particles from smokestack exhaust. That could make plug-in hybrids an environmental improvement over conventional cars and their tailpipe emissions. “Could” is the key word, however. Most American power plants aren’t equipped with advanced environmental controls, especially carbon dioxide capture technology. Coal-fired power plant owners have consistently resisted retrofitting their plants with the highest levels of pollution control technology because they say it would drive up the cost of power. In some cases, the government has backed them up. The Department of Energy reported in 2008 that existing carbon dioxide capture technology isn’t cost effective on large power plants. Not surprisingly, there have been no government mandates for cleaner coal-fired power.

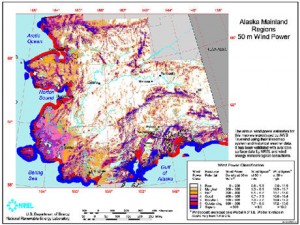

Can plug-in hybrids or my electric lawnmower make sense while coal generates 49 percent of America’s electricity? Yes, there are two reasons why plug-in hybrids are still a good idea. The first is that emissions control technology will get cheaper and more efficient if the federal government mandates it, which is the only way to create a market for it. The second is that plug-ins change how we think about our cars, and for the better. With wind, solar and biomass power gaining momentum, the grid will get greener. As it does, plugging in will make more and more sense than filling up. It will probably take a long time before conservation and renewable energy take a significant bite out of coal’s generating capacity, but it’s going to happen.

In the meantime, I think I’ll just let my grass grow longer and avoid the mower question altogether.