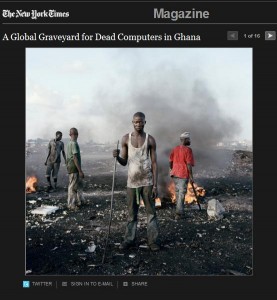

What are the right words for these photos of human beings, including children, working and, apparently, living amid electronic waste in the Ghana slum of Agbogbloshie?

Of course, there are none.

These images first appeared in the New York Times Magazine a month ago. I still see them every day, imprinted on every electronic device I see, whether in my pocket, on my desk, in my living room, stuck in my ears or in a chirpy television ad.

The photographer is Pieter Hugo, who writes on his website that the inhabitants have no name for the pit where they burn the old computers to extract metal for resale.

Their response is a reminder of the alien circumstances that are imposed on marginal communities of the world by the West’s obsession with consumption and obsolesce. This wasteland, where people and cattle live on mountains of motherboards, monitors and discarded hard drives, is far removed from the benefits accorded by the unrelenting advances of technology.

The slideshow is one of the most effective examples of communication in the interest of cleaner technology that one could ever imagine.

Some 53 million tons of electronic waste was generated worldwide in 2009, according to ABI Research. About 13 percent was recycled. E-waste, along with its hazardous material components, ends up in places like Agbogbloshie – and China, India and Indonesia – mainly because it’s cheaper to smuggle waste to poorer countries than recycle it according to emerging global standards and laws.

“Now we are collecting far more, but they can’t prevent it from going offshore,” Jim Puckett, director of the e-waste watchdog group Basel Action Network told the Times. “People talk about ‘leakage,’ but it’s really a hemorrhage.”

E-waste contains dangerous lead, nickel, cadmium and mercury. In the United States, 23 states have passed mandatory e-waste recycling laws, most of which make electronics manufacturers pay for recycling. Many municipalities also have aggressive recycling programs. Toronto, for example, is promoting its e-waste recycling program with video in stark contrast to Hugo’s photos.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8Es9tWXZgw

(Are they actors playing schlubs or schlubs playing actors?)

Deliberately grating and based on we-want-your-gold TV ads, the campaign lacks any of the grandeur in the Ghana photographs. In fact, the juxtaposition couldn’t be more jarring. But on its own merits, it’s pretty effective. To be honest, Chuck and Vince cracked me up. But I wasn’t laughing this morning when I left my old computer monitor on the curb.