I see so many windmill blades I feel like Don Quixote. There are at least five windmills – turbines we call them now, since they’re only milling electrons – within a 20-minute bike ride of my doorstep. These devices hint at the appeal, promise and challenges of wind power as a major energy source for the country and the world.

A trio of turbine towers spikes the farmland just up the road in Eliot, Maine. Although the proud owners expect an eventual payback, are receiving tax credits, and are putting a few kilowatts back into the grid, their motives are largely ecological: In the first month, John Sullivan’s 2.4-kilowatt[1] turbine “saved 120.4 pounds of CO2 from going in the air.” That’s the amount he figures a coal-powered plant would have pumped out making that electricity.

A trio of turbine towers spikes the farmland just up the road in Eliot, Maine. Although the proud owners expect an eventual payback, are receiving tax credits, and are putting a few kilowatts back into the grid, their motives are largely ecological: In the first month, John Sullivan’s 2.4-kilowatt[1] turbine “saved 120.4 pounds of CO2 from going in the air.” That’s the amount he figures a coal-powered plant would have pumped out making that electricity.

Unfortunately, the next town over, Kittery, is dismantling the 50-kilowatt turbine it erected in 2008 and returning it to the manufacturer for a refund, citing “underperformance” of the project. Trees and buildings created turbulence no one had accounted for, and the tower was producing only 15 percent of its projected power.

But there’s more hope back in Eliot. East of the farms, on the banks of the Piscataqua River, deep sea engineer Ben Brickett has been developing a turbine that turns in a breeze as gentle as 2 mph. That’s big, because low-wind days are the bane of traditional turbines. Called a variable force generator, Brickett’s invention converts wind directly into electricity, bypassing the conventional gearbox. Unlike other turbines, he says, it also manages to produce power in proportion to the wind speed, up to 60 mph. His company, Blue Water Concepts, is deep into prototype testing and is attracting interest from academia and manufacturing partners.

These are just a few small examples of how the Unites States has come to be the world leader in wind power with the fastest-growing capacity.

A mighty wind

The U.S. wind energy industry installed a record-breaking 8,500 megawatts of new wind-generation capacity last year, enough to serve more than 2 million homes, according to the American Wind Energy Association. That brought the country’s total capacity up to 23,500 megawatts and pumped $17 billion into the economy. The new projects accounted for roughly 42 percent of the entire new power-producing capacity added in 2008. It was like taking more than 7 million cars off the road.

The country has more than enough wind resources to reach a 20-percent wind energy contribution to the US elecrtricity supply by 2030, according to a DOE report. We’re currently at 4 percent for wind, biomass, geothermal, solar, and miscellaneous sources combined.

As this DOE map shows, the best wind is on the coasts and in the plains states. Texas leads the country with the most installed wind-based capacity by a wide margin, followed by Iowa, California, Minnesota and Washington.

Without losing sight of our tremendous progress, to follow is a list of obstacles impeding even more robust wind development. Anyone promoting wind, whether a new turbine design or 500-megawatt wind farm, needs to consider these obstacles as they set out on their crusade.

Infrastructure

The country needs transmission systems that can shuttle power from rural wind farms to urban centers as well as load balancing installations that enable regions to consume a mix of generation sources.

Aesthetics

Green, in addition to being good, is fashionable. So your neighbor may never be more welcoming of the sight of a windmill, or fleet of them, on your roof or farm. That said, there’s plenty of resistance. The $900 million Cape Wind project slated for Nantucket, Mass., has dragged on in permitting, politics and litigation since 2001. Viewshed impact is high on opponents’ list of concerns. So why not site wind farms on sparsely populated land? That’s not so simple either, as a Wyoming farmer is finding out.

Ecology

Ten thousand birds, including 80 golden eagles, die every year at a California wind farm near San Francisco, according to a study by the local community development agency. Wind proponents blame that carnage an unlikely convergence of factors, including bad siting and older turbine technology. On average, they say, wind power’s avian toll is extremely low.

Noise

No doubt about it, windmills make noise. But the key questions include: How loud? Is the sound of whooshing blades a bad noise? How far away are you? How fast is the wind blowing? Wind proponents put windmill noise in the decibel range of household background noise or the sound of trees and leaves rustling on a blustery day.

Taxes

The government (i.e., taxpayers) has begun issuing $500 million in grants to spur wind energy development as part of the economic recovery package. They’re a double-edged sword for people worrying about personal and national debt.

Foreign Investments

One company with Spanish DNA has received more than half of that $500 million grant money, says the Environmental News Service. Too many reports like this won’t sit well with the public.

The communications strategy

So what does this all mean for the inventor or company promoting wind? The good news is there’s abundant popular support and a persuasive case for wind and other renewable energy sources. Yet, as with any complex technology that needs to go in someone’s backyard, there is bound to be wariness, if not opposition, to siting proposals.

Consequently, any development effort requires a solid communications plan born out of this strategy:

- Identify all the potential benefits of a project, not just those in your market segment or locale. Include the benefits of wind to the planet.

- Talking points promoting your project are just a start. You need data, and there is plenty of it out there. As you can see by the links in this blog, the American Wind Energy Association is a great place to start.

- Develop content up front that documents all of the benefits. Main audiences include the public, planners and regulators.

- Connect with advocacy organizations, politicians, utilities, business groups, landowners, conservationists and educators who are likely to favor your project.

- Anticipate all potential concerns and prepare to address them squarely. Avoid defensiveness or reactivity. Listen and talk rather than argue. Some skeptics just need to be informed.

- Depending on what you’re proposing, you could end up with a lot of energized opposition. Make sure you have the arms, legs and content to swiftly and effectively address the concerns.

- If you believe in your project, stay the course.

…

Some helpful resources from the American Wind Energy Association:

Handbook for permitting small wind turbines:

Talking points on the benefits of wind energy.

Handbook for commercial scale siting.

Wind power outlook for 2009

[1] A 5kW turbine is sufficient on average to power a home. Variables include wind speed, turbine height, terrain and home energy usage, according to the American Wind Energy Association.

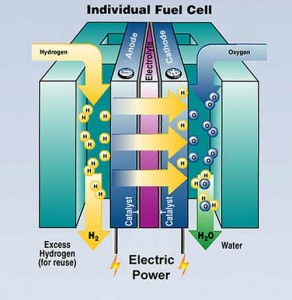

Even when they hit the market in earnest, however, I’m skeptical that hydrogen cells will revolutionize the motor vehicle industry, as hyped. Hybrid gas/electric technology is years ahead of hydrogen cells in the automotive market, and auto companies are making huge strides in hybrid technology. Just last week at the Frankfurt Auto Show, Volkswagen unveiled a two-passenger concept car that gets 240 miles per gallon. Hydrogen fuel cell makers, by comparison, don’t even have production models on the road yet.

Even when they hit the market in earnest, however, I’m skeptical that hydrogen cells will revolutionize the motor vehicle industry, as hyped. Hybrid gas/electric technology is years ahead of hydrogen cells in the automotive market, and auto companies are making huge strides in hybrid technology. Just last week at the Frankfurt Auto Show, Volkswagen unveiled a two-passenger concept car that gets 240 miles per gallon. Hydrogen fuel cell makers, by comparison, don’t even have production models on the road yet. Hydrogen cells might be the greenest technology for powering vehicles, but history has proven time after time that incumbent technologies are hard to beat if they’re cost effective and do a good, if not great job. Look at Ethernet versus ATM (asynchronous transfer mode) in networking. ATM was faster and could support more services, but Ethernet was capable, inexpensive and well established by the time ATM came along. Ethernet remained the dominant local area networking protocol, but ATM found its niche in wide-area networking. Hydrogen fuel cells are looking at a similar situation. Hybrid vehicle technology is here and now and it yields good fuel economy at a reasonable environmental cost. That’s a moving target that hydrogen fuel cells can’t hit. Better to focus on a market where their adaptability makes them the technology to beat.

Hydrogen cells might be the greenest technology for powering vehicles, but history has proven time after time that incumbent technologies are hard to beat if they’re cost effective and do a good, if not great job. Look at Ethernet versus ATM (asynchronous transfer mode) in networking. ATM was faster and could support more services, but Ethernet was capable, inexpensive and well established by the time ATM came along. Ethernet remained the dominant local area networking protocol, but ATM found its niche in wide-area networking. Hydrogen fuel cells are looking at a similar situation. Hybrid vehicle technology is here and now and it yields good fuel economy at a reasonable environmental cost. That’s a moving target that hydrogen fuel cells can’t hit. Better to focus on a market where their adaptability makes them the technology to beat.