Affable and inspiring Gary Hirshberg, chairman, president and CE-Yo of Stonyfield Farms was the featured speaker at Saturday’s University of New Hampshire graduation. The company makes the number-one selling brand of organic yogurt and is the number-three overall yogurt brand in the US according to Fortune magazine. Through its Profits for the Planet program, Stonyfield gives 10% of profits to environmental causes.

Here are memorable takeaways from his talk:

Here are memorable takeaways from his talk:

- “We allowed ourselves to believe in a sort of modern day mythology about the infinite resilience of our finance system, and to allow greedy, short-term thinking to get the upper hand. In a nutshell, we borrowed money we didn’t have, to buy stuff we didn’t need.”

- “We are seeing signs of failure in every single aspect of our relationship to the planet … if we stopped all fossil fuel burning this afternoon, the Earth’s fever would continue to mount for 40 more years before it began to break.”

- “How far an item travels, is actually a very minute percentage of the footprint of an apple, yogurt or bottle of beer. The far larger footprint is in how the product is grown, that is the type of agriculture accounts for more like 50-60% of the carbon footprint. In other words, buying organic from a long distance may be far more carbon-friendly than buying non-organic locally. The point is, we need to be sure our brains are as engaged as our hearts when making big decisions.”

- “I have learned that, whatever you choose to do, there is no point in producing the same quality as anyone else. In fact, that is likely a strategy for failure, for you are almost certain to be out-competed by someone who is better capitalized.”

- “At a societal scale, those of you who question conventional thinking will be in the best positions to seize the next wave of jobs and economic opportunities. Consider for instance, that with the amount of sunlight that strikes the US each day, we would need only 10 million acres of land – or only 0.4% of the area of the United States – to supply all of our nation’s electricity using solar photovoltaics.

“When you consider that the US Government pays to idle approximately 30 million acres of farmland per year, you can see how confused our priorities have become.”

“When you consider that the US Government pays to idle approximately 30 million acres of farmland per year, you can see how confused our priorities have become.”- “Success will be when you finish eating the yogurt, you will eat the cup.”

- “Solar isn’t just for Arizona anymore, either; right now in New Hampshire there are homes powered completely off the grid – built at competitive costs. For less than half the normal garage roof space, you can power your house with no fuel, no pollution, and no ice storm outages. Soon it’ll be down to one-quarter of that garage roof. And we haven’t even talked about solar hot water, which is even cheaper than solar cells, or wind power, which is cheaper too. Best yet, these power sources are built, installed, and maintained locally, right here in America, unlike the billion dollars per day we ‘export’ out-of-country for oil, for example.”

- “Renewable technology isn’t just a energy issue, it’s a global competition. We don’t have a natural monopoly on sunlight or wind, and the Danes, Germans, and increasingly, the Chinese ‘get it.’ They aim to be the energy technology vendors to the world, and—having paid more attention to it than we have—they’re as good or better than we are.”

- “Questioning conventional authority is a powerful way to succeed in business and in life. A couple of guys from UPS once asked ‘why not try to avoid left-hand turns,’ with their 95,000 big brown trucks.”

- “

What we discovered from doing good is a new business formula that is now being mimicked by the largest companies on earth…. when you make a better, higher quality product, you leap all the way to loyalty without having to spend as much on advertising…. When you make it better, you get loyalty. And with loyalty comes the most powerful purchase incentive in commerce—word of mouth.”

What we discovered from doing good is a new business formula that is now being mimicked by the largest companies on earth…. when you make a better, higher quality product, you leap all the way to loyalty without having to spend as much on advertising…. When you make it better, you get loyalty. And with loyalty comes the most powerful purchase incentive in commerce—word of mouth.” - “I can assure you that there will be more jobs in renewable energy, energy efficiency, preventative health care, organic/non-toxic agriculture, textiles and cleansers (I have yet to meet the consumer who prefers to eat the yogurt with more pesticides or synthetic hormones than in the traditional fields.).”

- “The whole notion of service is very attractive to smart employers. From a practical perspective, those of you who volunteer and give your time and energy to work on positive change are exactly who we CEO’s want to hire.”

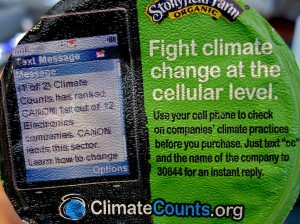

- “Don’t forget that as consumers, we wield enormous power to choose the polluting, consumptive and failed ways of the past or the renewable and sustainable ways of the future too. When we purchase anything, we are voting for the kind of communities, society and planet we want. And I have learned that corporations spend billions of dollars to tally those votes.”

- “We stand at the edge of the next wave, the sustainability revolution in which we use green chemistry which leaves behind no toxic residue, cradle to cradle technology which generates no waste, renewable energy with no carbon footprint, industrial ecology with waste from one process being the food for another, will be the norm.

- “Personally, I feel there is no greater societal priority than to embrace the conversion to renewable energy and organic food production with all of the climate, ecological and health benefits. When people tell me that organics is not proven, I respond that it is the chemicals that are not proven, but the early results are poor as we face an epidemic of cancers and preventable disease. The same is true of our energy policy, which has been driven by generations who have grown up in the oil and coal business and believe that mining the earth’s crust is the only way to fuel our needs.”