Rhetoricians call it “arguing against interest.” In simple terms, it’s a good way to build credibility fast. You readily admit a weakness in yourself or your argument to actually advance your larger case. I swear to you, your honor, I had no role in the killing of which I’m accused. I was out of state, uh, delivering a shipment of drugs. This mechanism causes the audience to wonder, who but an honest-to-God truth teller would disclose something so damning?

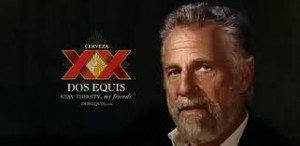

Arguing against interest can be a powerful tool for building brand credibility. Look at Domino’s Pizza, now publicly admitting their old pizza was terrible. Or Dos Equis: What, the Most Interesting Man in the World doesn’t always drink beer? This is a beer commercial!

Arguing against interest can be a powerful tool for building brand credibility. Look at Domino’s Pizza, now publicly admitting their old pizza was terrible. Or Dos Equis: What, the Most Interesting Man in the World doesn’t always drink beer? This is a beer commercial!

What makes arguing against interest so powerful is its stark contrast against the vast majority of communication that argues, often lamely, in its own interest. Ads, websites, press releases and corporate blogs dump buckets of overstated goodness on a cringing consumer. You know, if you buy the right camera, you’ll shoot National Geographic quality images. With the right diamond necklace, you’ll be back on your honeymoon, and with a fabulous spouse.

Not saying such images aren’t seductive, but overstatement is the Achilles heel of marketers who are mired in old-school corporate communications. While gilding the lily has never been a great persuasion technique, today’s audiences despise it. They are sophisticated, discriminating and skeptical, if not cynical, driven largely by social media.

Case in point

A wonderful example of a brand arguing against interest to deepen credibility is Patagonia, the maker of outdoor apparel for skiers, rock climbers and campers (it’s like a crunchy Timberland). They’re not just sprinkling their content with a few aw shucks asides, they’re actually building their brand around a concept that, at first glance, is directly opposed to their own goal of making money.

A wonderful example of a brand arguing against interest to deepen credibility is Patagonia, the maker of outdoor apparel for skiers, rock climbers and campers (it’s like a crunchy Timberland). They’re not just sprinkling their content with a few aw shucks asides, they’re actually building their brand around a concept that, at first glance, is directly opposed to their own goal of making money.

The company’s Common Threads Initiative is urging customers to buy less clothing, wear it longer, repair it instead of throwing it away, and when it’s worn out, hand it back to Patagonia for reuse or recycling.

… to wrest the full life out of every piece of our clothing, the first three of the famous four R’s are equally important – to reduce, repair and reuse as well as recycle.

Under reduce, the company is calling on consumers to “buy what you’ll wear, and want to keep long enough to wear out” in order to “get by with fewer clothes.”

Under repair, it’s offering to fix zippers for free if the garment has enough life left in it.

(The company already has a recycling program that’s collected 39 tons of used clothes.)

This initiative is like General Motors telling you to drive your clunker into the ground because it’s the right thing to do. Of course, Patagonia is a for-profit business and commercial brand. So their larger goal with the Common Threads Initiative, one assumes, is to deepen customer loyalty, reduce raw material costs, and put a noble face on plain ol’ customer service (I mean, they’re probably going to fix zippers anyway).

Deep in the content

Deep in the content

All this is clearly a flavor of cause branding, but Patagonia is taking it to the next level with a generous dose of argument against interest throughout its public content. For example, Patagonia recently underwent a corporate social responsibility (CSR) audit. A nonprofit watchdog organization took a hard look at their operations. Patagonia blogged about the audit in great detail. The post mentions a couple of instances of where the company fell short in the review (arguing against interest). They even admit they’re a founder of the group that was auditing them. Who even blogs about audits, much less the negative findings and conflicts of interest? Now you might be asking, where’s the marketing value in this? What comes through is not Patagonia’s warts, but its seriousness about being green and transparent. It’s as authentic as you can ever expect communications to get. And utterly believable.

Another example: In writing about the new Common Threads Initiative, Patagonia talks about its five-year-old recycling program, whose goal was to make all Patagonia clothes recyclable within five years. “This we will achieve in fall 2011,” Patagonia writes, “a year behind schedule.” Another argument against interest. This line is just sitting there in the copy, no excuses, no tortured transitions, just a fact. You make the call. This kind of statement is convincing.

Patagonia has a minisite, The Footprint Chronicles, that drills into the origin of Patagonia garments. Click on the Merino 2 Crew sweater and learn that the wool is sustainably ranched, the dye is okay, and the factory is okay, but the wool travels 16,280 miles from sheep to store. “This is not sustainable,” the Patagonia website tells us. Who says this about their own supply chain? Nobody. In how many instances is it true? All the time, presumably. Patagonia cares so much about getting it right they readily admit what they’re still getting wrong.

In another Patagonia post, a blogger admits his orthopedic problems ruined his climbing adventure. One would expect tales of glory. But while Nike has LeBron and UGG Under Armour has Tom Brady, here’s Patagonia speaking through a guy whose arm keeps dropping out of his shoulder socket.

If all this arguing against interest sounds like overkill, it’s only because we’re calling out the exceptions to the rest of the Patagonia content, which as you would expect is generally favorable to the company. But this positive content is all the more believable next to a few well-conceived arguments against interest.

By acknowledging that’s nobody’s perfect, starting with yourself, you can strike the perfect note.