I love renewable energy stories. We know that if we can reduce our reliance on fossil fuels, we can reduce global warming, our utility bills and, one hopes, our military presence in the Middle East.

But renewable energy stories frequently disappoint. What starts out like a success story turns out to be merely a hint at renewable energy’s potential. Too often, the project isn’t quite there yet. It’s merely proposed, or it’s in the demonstration stage, or it’s underwritten by a one-of-a-kind grant, or it’s only a tiny improvement on traditional methods.

But renewable energy stories frequently disappoint. What starts out like a success story turns out to be merely a hint at renewable energy’s potential. Too often, the project isn’t quite there yet. It’s merely proposed, or it’s in the demonstration stage, or it’s underwritten by a one-of-a-kind grant, or it’s only a tiny improvement on traditional methods.

That’s why I’m delighted to hear that a local developer has invested in geothermal to heat and cool a four-unit residential condominium now on the market. According to the local paper, the holes have been dug, the pipes have been laid, and the condos are more than 90 percent complete. It looks like a rare marriage of renewable energy and the free market: private money going into a private project (with any tax credits going to the eventual homeowners).

So while the success story isn’t complete, it’s real. Explaining his rationale for the project, developer Steve Kelm said the owners will never have to worry about rate shock of fluctuating heating oil prices: “I’d rather be ahead of the curve.”

The payback on a project like this is about five years, estimates Andy Livingston, chairman and CEO of American Ecothermal Inc., also of Portsmouth, which installed the geothermal “wells.”

How does geothermal heating and cooling work?

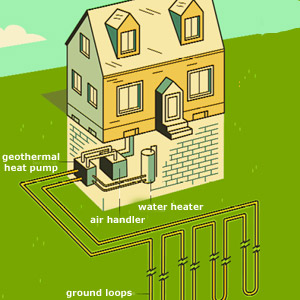

Geothermal uses heat from the earth’s core and sun-baked surface to heat homes in the winter and cool them in the summer. You need a geothermal heat pump (GHP), which circulates a carrier fluid through underground pipes. In the winter, the heat pump uses electricity to extract heat from the ground-warmed fluid, sending re-chilled fluid back through the ground to pick up more heat. And the cycle continues. The principle is similar to an air conditioner or refrigerator. This approach is 48 percent more efficient than the best gas furnaces and more than 75 percent more efficient than oil furnaces, according to the EPA.

To cool a home in the summer months, switch the direction of the heat flow, and the same system can extract heat from the air, thereby cooling it.

What are the benefits?

Geothermal heating and cooling offer a potential large reduction in energy use, peak demand and utility bills. Aggressive deployment of GHPs could nearly halve the need for net new electricity capacity needed by 2030, according to a U.S. Department of Energy study. It could reduce electricity bills by as much as $38 billion.

More stats from the Geothermal Heat Pump Consortium, the non-profit trade association for the GHP industry:

More stats from the Geothermal Heat Pump Consortium, the non-profit trade association for the GHP industry:

- Operating 100,000 geothermal heat pump units over 20 years would be the greenhouse gas/carbon reduction equivalent of taking 58,700 cars off the road or planting 120,000 acres of trees.

- Owners can expect savings of 30 to 70 percent in heating mode and 20 to 50 percent in cooling mode compared with conventional systems.

- GHPs reduce energy consumption and corresponding emissions by 40 to 70 percent over traditional heating methods (e.g., furnaces).

And there are concrete tax incentives. The IRS is offering tax credits for 30 percent of the spending on geothermal heat pump equipment, including labor. Installing a $12,000 geothermal heat pump system would give you a $3,600 credit.

Geothermal in the works

We’re just getting started with geothermal heating and cooling. The United states has more than 600,000 GHP units, the largest installed base in the world, but many European companies are ahead on a per capita basis, according to the DOE.

A Reno casino, the Peppermill Resort Spa, has tapped an underground aquifer holding 170-degree water to heat a 17-story hotel tower, including restaurants, 1,600 rooms, and the water for the sinks and showers. Owners are predicting $1 million in a year in savings with an eight-year payback.

An Iowa town is using part of a $1 million community development grant to create a shared geothermal heating and cooling system for the downtown.

Some homeowners are designing homes that combine geothermal with passive solar and knock $1,000 off their utility bills. This geothermal/solar design involves solid wood walls, an airflow envelope just inside the walls, and lots of windows on the southern exposure.

Meanwhile, there’s an entire separate industry using geothermal to produce electricity. That’s for another post, but one exciting possibility is in oil production. Oil extraction is accompanied by non-petroleum hot fluids that can help power field equipment. “With an estimated 10 barrels of hot water produced along with each barrel of oil in the United states, there is significant resource potential for this technology,” says the US DOE.

Bring it on. It’s time for more success stories.